Earlier this week, something in my Twitter feed caught my eye. Aaron Moser, a journalist with the Gun Crisis project (this is a group of individuals dedicated to reducing gun violence whom I follow in an effort to intellectually challenge myself and flesh out my own beliefs on firearms… as their positions on the issues often run contrary to my own views) tweeted about “Smart Guns” and a story that CNN was running.

To those who are not aware, “smart gun” technology has been a goal of many researchers for some time. Despite much of the public only seeing this concept for the first time in the latest James Bond film* efforts have been underway for well over a decade now to make small arms which will only fire if they are in the hands of an authorized user/owner. Relying on an assortment of RFID and biometric technologies, those who research smart guns seek to devise arms which will operate reliably and safely, as long as an authorizing token (such as a wrist strap or ring) is next to the frame or as long as an authorized and enrolled individual’s fingerprints or hand geometry can be recognized by the handgrip. Naturally, there is great interest in this sector by entrepreneurs, governments, and those who keep abreast of the ever-changing landscape of firearms.

* long-time fans of 007 might actually recall that it was decades ago, in 1989’s License to Kill, that Q Branch outfitted James Bond with a gun that would only fire in his hands!

Two things have proven rather constant throughout the life of these sort of projects:

1. They are treated as interesting curiosities by the press and media, with most reports focusing on future potential and current experimental results

2. Virtually no police agencies or militaries have adopted them, and private civilians speak out loudly against them (or, rather, against any regulations that would require such features in all privately-owned guns)

Often, those who encounter these reactions appear puzzled. (NOTE – I am not suggested that Aaron was puzzled by this. He is rather abreast of most firearm-related news and by all accounts is well-read and familiar with most trends in the industry.) If guns such as these could prevent accidental discharge or use by unauthorized parties (like criminals) then why wouldn’t there be a greater clamor for them?

Full Disclosure: One of the research institutions which has dedicated considerable time and effort toward the development of smart gun technology is the New Jersey Institute of Technology. That is one school from which I hold a degree. Although I was enrolled during the time of some of this research, I did not interact with the students or staff who were involved.

.

My Prediction

I thought about this, and my own personal conclusions can be summarized as follows: While historically, the public at large has shown an overwhelming trend of adopting the same firearms used by current-era police and soldiers, such a trend will not be seen with smart guns. Some day, smart gun technology may become accepted as reliable enough for use by police officers (i predict it will NEVER become adopted in the military) but if and when that happens, our history of seeing civilians adopt whatever their local officers carry will not continue.

Why is this the case? Well, let’s take a look at the previous occasion when a monumental shift was seen in terms of gun ownership: the move from revolvers to semi-automatic pistols.

.

The Next Big Thing

It has been argued by many that Samuel Colt’s introduction of a mass-produced, affordable revolver just after the middle of the 19th Century revolutionized small arms. His reliable and easy-to-operate sidearm capable of repeated firing and simple reloading instantly changed the landscape of guns in America. It was quickly adopted by the military (at least by officers, who had greater autonomy and personal income) and then by police departments as the 1800s concluded. Unbeknownst to many people, however, is the relatively short-lived time frame during which the revolver was the exclusive option for a repeating-fire sidearm. Only a few decades after the Colt Patent Fire-Arms Manufacturing Company started churning out Peacemakers, John Browning developed what would become the modern standard for handguns around the world: the semi-automatic pistol.

By nearly all measures and means of evaluation, pistols are a significant step up from revolvers… especially for those whose vocation entails frequent use of firearms (police, military). Increased capacity, faster reloading, and generally an easier trigger-pull are features by which all pistols tend to eclipse their revolver counterparts.

Why, then, did police departments take such a comparably long time to adopt them? Much of it has to do with the counter-arguments: that revolvers are “easier to use” (a claim that’s been debated) or “more reliable” (that’s also disputed, but to a lesser degree)… and also a great deal of this was pure technological momentum. Having come first to market, revolvers were entrenched in the consciousness of many people as the right tool for the job. It took a lot of time for attitudes to change, and there were a variety of forces shifting the tide.

During the start of the 20th century, virtually all police departments relied on revolvers, chambered in .38 caliber in virtually all instances. Although John Browning’s first automatic pistol debuted in 1896 and his truly legendary locked breech action design (a.k.a. short-recoil operation as opposed to blowback) captivated the world’s militaries starting in 1911, police departments continued to rely almost exclusively on revolvers for nearly an additional three-quarters of a century.

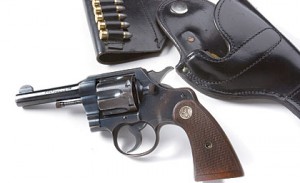

the classic .38 caliber police revolver, standard issue for nearly a century… virtually every single police officer seen in public had one of these on their hip.

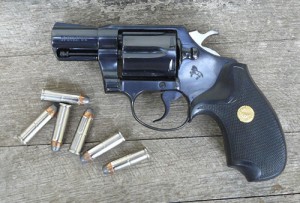

a .38 caliber “detective’s special” … little more than the same revolver shown above with a snub-nosed barrel. This would be carried by a plainclothes Detective or a desk Sergeant, etc.

Whether they worked a desk or walked a beat, nearly all men and women** with badges carried .38 caliber revolvers.

** At that era in American history both jobs were routinely staffed exclusively by men, the primary exception being during World War II… although even then most women hired by departments worked at station houses as dispatchers or primarily clerical staff. It was not until the 1950s that female officers started becoming visible in uniform on the streets.

Criminals, of course, made use of whatever firearms they deemed as best-suited to their particular aims. Unconstrained by budget, policymakers, or institutional thinking, many criminals (particularly the well-financed gangsters of the 20s and the Mafia) adopted semi-automatic pistols with greater ease than their adversaries… police and G-men. That last point leads to a rather noteworthy detail of history: Special Agents in charge of combating rum-runners and bootleggers were among the first law enforcement types to begin carrying higher-capacity and higher-caliber sidearms by department policy. Full Disclosure: my grandfather was a Special Agent during the Prohibition years. He had to turn in his primary service weapon upon retirement, but I still own his small backup guns… which were pocket revolvers.

.

Eventually, however, it became evident that even lowly street criminals were increasingly well-armed (a trend that was highly influenced by the crack boom of the 1980s and the previously-unheard-of profits for gangs at that time) and police departments began a significant migration to semi-automatic pistols for their officers’ use.

a Smith & Wesson model 39… reported by many to be the first semi-auto pistol adopted by a law enforcement. The Illinois State Police were using these officially as early as the 1970s. Most other law enforcement agencies wouldn’t follow suit until the 1980s, however.

The Beretta 92F… one of the first widely-accepted pistols to be adopted by police in the USA. Ironically, it was this same pistol that replaced the Springfield Armory model 1911 pistol for our military in 1990… our armed forces had already been using semi-auto pistols as sidearms for decades by that time.

A first generation Glock 17… pistols from this manufacturer would come to epitomize police sidearms during the latter decades of the 20th century.

Once the trend towards use of pistols became widespread, there was no turning back. Throughout my teen years in the 80s & 90s I interacted with many police officers (casually, not in custody, heh) and my interest in firearms would regularly be the impetus for conversations about their carry weapons. Time and time again, I heard the same refrain when I asked what they were issued: SIG Sauer.

a SIG P226 – the pistol that became synonymous with law enforcement during my formative years

the SIG P228 and P229 (pictured) are compact variants of the legendary pistol above. They remain to this day a favorite of many police departments and are also the preferred sidearm for almost all government agents such as FBI, DIA, etc.

a Generation 4 Glock pistol. What’s old is new again… the Glock model 22 is now the most widely-used police sidearm in America, by a considerable margin.

So, during this time of changing Police Department policies, what were civilians purchasing from their local gun shops? It may be surprising to some, while common knowledge to others, that the average citizen has always tended to favor whatever guns were in common use by local police officers.

When wheelguns were the standard, civilians bought revolvers. When departments across America transitioned to semi-autos, pistols became the most-sold items at gun stores around the country. The same trend has taken place with long arms, as well. The shotguns and rifles in American homes have always been the same ones in arms lockers at local precinct houses. New ammunition, likewise, has seen similar patterns of adoption.

Copper jacketing over top of conventional lead nose bullets became a standard means of protecting against melting of the lead given the higher temperatures and velocities of modern ammunition

Hollow-point bullets — designed with the aim of both increasing stopping power while decreasing the potential for ricochet or over-penetration — first became available around the turn of the century, but did not see widespread adoption by Police Departments until the 1970s and 1980s. Now, they are universally accepted as the most adequate self-defense rounds for handgun use by both police and civilians.

.

Blue Uniforms on the Silver Screen

I find it interesting to take a look at the history of handguns in America through a rather unconventional lens: Hollywood. While critics of film often bemoan the lack of accuracy and realism present in many blockbuster movies, there is one aspect of our gun culture that has historically been very accurately-portrayed in cinema: the types of guns used throughout history. Say what you will about violent tales from screenwriters or gory camera footage from certain directors, but the propmasters of all major studios and even small, independent companies tend to take very seriously the task of accurately representing how police, criminals, and even just private citizens have chosen to arm themselves over the years.

A brief walk through some of the best cops-and-robbers cinema of the 20th century shows the same exact trend that was playing out in police departments across America — particularly the transition to semi-automatic pistols which began during the late 1980s.

.

Era One – The Wheelgun is King

Bullitt (1968) – Steve McQueen’s lead character carries a Colt Diamondback. Other police serving with him rely on Colt Detective Specials or Smith & Wesson model 58s… all revolvers. One criminal in this film has the legendary semi-auto Colt 1911 pistol.

The French Connection (1971) – Most police in this classic film, including Gene Hackman himself, carry Colt Detective Special revolvers. As with Bullitt above, other police are seen with standard issue Smith & Wesson revolvers, also. A hitman in the film has a Colt automatic pistol, and the Mafia is shown to have Beretta Model 70 semi-autos.

Dirty Harry (1971) – Hardly a single movie-going member of the public in the early 70’s was unaware of Clint Eastwood’s now-iconic revolver, a Smith & Wesson model 29 chambered in .44 Magnum. Another police inspector in this film also carries a revolver: a Colt Detective Special.

Serpico (1973) – Here we see an interesting glimpse of both sides of the law, sometimes through the eyes of the same person. Uniformed police, including Al Pacino’s title character, carry Smith & Wesson model 36 revolvers, Colt Offical Police revolvers, and Smith & Wesson model 10 revolvers. While working undercover, Officer Serpico opts to carry a Browning Hi-Power, as he is attempting to not portray himself as an officer. (Another reason for his choice was this pistol’s ability to hold fourteen 9mm rounds. Serpico was seeking greater firepower after becoming the subject of harassment while he fought police corruption.) Likewise, we see a drug dealer with a Colt Woodsman, another semi-auto pistol.

.

Era Two – Transitional Years

Lethal Weapon (1987) – In the seminal work that came to utterly define the buddy cop genre, the clash between “old timer” and “young kid” was played out both in the dynamic between Mel Gibson and Danny Glover’s attitudes and also seen in their choice of firearms. Young Officer Riggs’ Beretta 92F stood in stark contrast to the aging Det. Sgt. Murtaugh’s Smith & Wesson model 19. The rest of the film featured a mix of assorted revolvers and automatics in the hands of both criminals and law enforcement alike… bearing witness to the changing trends at this time.

Point Break (1991) – Another film to take the same angle as Lethal Weapon, here we see the fresh-faced FBI Agent Utah (Keanu Reeves) with a SIG P226, the flagship pistol from the line of guns that would come to define the entire Bureau, while his haggard and long-serving partner carried a Charter Arms Undercover (a revolver). Also, much as with Lethal Weapon, other criminals and police are seen with a mixed assortment of both revolvers and semi-auto pistols.

The Silence of the Lambs (1991) – One more film in our list highlights the shifting tide towards the adoption of semi-automatic pistols that took place in the late 1980s. The leading actor in this film, Jodie Foster, was always seen carrying a Smith & Wesson model 13… which in reality was the last revolver model to ever be issued by the FBI. Regular police officers also carry Smith & Wesson revolvers, but SWAT personnel are shown with Browning Hi-Power pistols and an FBI agent in charge of a Hostage Rescue Team is shown with a Heckler & Koch P7 pistol.

.

Era Three – Pistols for All

Traffic (2000) – By the close of the 20th century, Hollywood was accurately portraying the almost total market penetration that semi-auto pistols had achieved in America. During the film Traffic, virtually all parties on both sides of the law were seen carrying pistols: a Colt automatic carried by Mexican police, an H&K automatic carried by a drug dealer, SIG automatics carried by assorted drug criminals, Glock model 17 and 19s carried by police and DEA respectively, SIG P228s carried by police, and even a hitman was shown with a modern H&K USPc. The only revolver in the film (a briefly-seen Smith & Wesson model 66) was carried by poor drug dealer in a ghetto neighborhood… a no doubt deliberate choice on the part of the film’s propmasters and armorers who were attempting to highlight this street criminal’s limited means and low status.

Training Day (2001) – A modern twist on the “young rookie paired with edgy veteran cop” genre, now in the 21st century we see both Ethan Hawk and Denzel Washington with semi-auto pistols (a Beretta 92F and a Smith & Wesson 4506, respectively). Other Berrettas and Glock pistols are shown in the hands of both police and criminals. Additional police carry SIG pistols, as well. Almost identical to the film Traffic, mentioned above, the only revolver shown is a Smith & Wesson model 19 snubnose… seen in the hands of a street criminal.

The Departed (2006) – As the start of this film focuses a great deal on officers in the field and in the Police Academy, there are numerous shots of SIG P226s (this pistol has been standard-issue for the Massachusetts State Police since 1987) and an Astra A-100 pistol. A Walther PPK pistol is seen being used for undercover carry, and a Barretta Cheetah pistol is carried by the crime boss in the city of Boston. The only revolvers in the film are carried by two very old-time criminals: a Colt Python revolver and a Smith & Wesson revolver.

.

Will the Trend of Modernization Continue?

Whether the changing tastes of American gun-buyers can be said to have been directly influenced by their local police officer friends or whether popular cinema was driving this trend (and, as we have seen, in such a case Hollywood was truly just mirroring the very real shifts in police culture throughout the latter part of the 20th century) it is undeniable that nowadays, purchases of new guns by civilians tend to be overwhelmingly of the semi-auto pistol variety.

Any misgivings or imperfections in this design of handgun have all but completely faded away, and in the modern landscape of small arms the venerable revolver is now resoundingly classified as an historical novelty. Nothing to be dismissed, of course — plenty of people will continue to rely on revolvers that have been in their possession or in their family for years and years to come, there is nothing wrong with that — but clearly this technology has been eclipsed by modern, short-recoil pistol designs.

So what of smart guns? Will they be the next major trend in handgun adoption?

Image of a prototype smartgun, with circuitry in the left side grip.

Close-up photo of the circuitry of a prototype smart gun.

Make no mistake, the concept of smart guns is not going away. Unlike other schemes to modernize handguns in a attempt to either make them safer or less useful to criminals (micro-stamping comes to mind as one of the most ill-conceived and unfeasible ventures that came and went in history), smart gun technology represents an area where there will be continued research for many years to come.

Indeed, it is quite possible that if this sort of firearm design can be proven reliable — it will have to be sufficiently-demonstrated to critics that not only will it prevent unauthorized use, but it will also NOT suffer from unexpected failure-to-fire… this second consideration will be a MUCH higher hurdle for smart guns to surmount in the eyes of skeptics — I predict that one day we might see smart guns adopted by police departments or prison officials.

Would such a shift in police firearm usage be mirrored in the civilian market much like previous trends were?

Not a chance.

.

Your Uniform and Your Daily Carry

Why do I feel so strongly that smart guns will never make the slightest dent in the civilian market even if they are widely-adopted by police? Simple: Below you see a depiction of a typical police officer and their interaction with their handgun.

Police officers have a daily routine with the following important characteristics:

- They often wear the same uniform consistently while on duty (even if this “uniform” is a suit or civilian attire if they are not a patrol officer)

- There is a very real chance that they will have to use their gun on any given day

- The vast majority of uniformed officers wear their sidearm prominently, in plain view (where it might be sized by a criminal)

- The profession of Police Officer is one which routinely involves encounters with criminals, potential criminals, or other unknown parties who might do harm

In short, individuals working in Law Enforcement are more likely than civilians to actually need to use their guns and they are far more likely than civilians to be wearing a standard set of clothing and equipment should such an occasion come to pass. The notion of remembering to wear an RFID enabled wristwatch or ring is not that great an encumbrance if your daily routine consists of putting the same clothes, belt, gear, hat, and badge that you wear every other workday.

Another consideration is that if you are serving in the company of other officers, it is overwhelmingly likely that all parties have their own personal firearms. Sharing or swapping guns might take place on the range… but in the field everyone relies on the firearm at their side.

.

Contrast that with the most typical way in which a private citizen is likely to make use of a gun…

Most citizens’ lives are nothing like the daily routine of a police officer:

- They wear whatever attire is comfortable and best-suited to their business that day

- Most citizens do not plan their day around the idea of having to use their gun

- Almost no citizens choose to open-carry a firearm, particularly in high-crime areas

- Most people lead quiet, simple lives and for them the possibility of being in a dangerous or violent encounter is quite remote

It’s complicated enough for some people to remember to transfer their wallet or mobile phone to their other pants, let alone thinking about putting on a special wristband in case you have occasion to need your firearm. This is to say nothing of concept illustrated by the above photo… someone who is awakened by a threatening noise late at night and might be wearing almost nothing at all. Even people such as myself who regularly make use of their right to carry a concealed weapon do not go around thinking (in spite of what some extreme anti-gun folk might believe) “today’s the day I might need to pull this gun out and use it.” Since concealed carry is far and away the norm for private citizens, the risk of someone flagrantly and brazenly stealing someone’s gun off their hip is remote.

Perhaps the most stark contrast between the lives of police and citizens when it comes to the use of guns, however, involves the likelihood of a privately-owned firearm being accessible to more than one party. I grew up in a home with guns. Everyone living in that house knew about said guns and everyone was more than adequately versed in shooting those guns. In the confusion and stress of the very unlikely scenario in which a homeowner’s gun might have to be loaded and trained on an intruder, it is often very unpredictable as to who exactly would be holding it. A husband or a wife? A boyfriend or a girlfriend? Even a son or daughter… all are equally-valid possibilities depending on the circumstances.

From the time I first moved out on my own, I have had one particular rule about the protection of my house: there will always be enough guns for each person living there to wield one shotgun and one handgun. After moving into the current rowhome where I now live in West Philadelphia, I continued with that metric. I purchased an additional shotgun. I also made certain that the other two housemates knew how to safely operate the defensive firearms in the house. My girlfriend has been staying with me more often. I made certain that she was fully-versed in the operation of my Mossberg 590A1 shotguns (her family preferred Remington 870s when she grew up).

No lesson was needed on any of the handguns since she has been shooting since she was a girl. She is more than familiar with revolvers, but her carry piece is a semi-auto pistol, just like mine. Well, not just like mine. I own H&K USP compacts. She carries a Walther. No, it is not a PPK. 🙂

In short, the fact that a violent encounter is far less likely for a private citizen coupled with the fact that the use of a firearm is far more likely to be during an unpredictable situation makes RFID-enabled smart guns wildly unsuited for private citizens… especially in the home.

Some of these arguments would be countered if all smart gun technology used biometric features as opposed to a wristwatch or ring, as long as it would be possible for the owner to easily enroll and/or delete however many authorized users they wish. Still, even then, I would predict more resistance than adoption.

Would citizens accept smart guns for daily carry if they exercise that particular right? I certainly don’t think so. There are two reasons, and both relate to economics.

1. Smart guns, if they are ever suitable for general use, are inevitably going to cost more. Police Departments might have the budget to offset this consideration, but private citizens don’t.

2. Furthermore, since for many private individuals their carry gun is also their home defense gun, the choice to use a smart gun when out and about would mean severely compromising one’s defensive possibilities within the home (unless, of course, everyone with a carry permit also chose to purchase additional guns… some for outdoors and some for keeping at the ready in the home.)

.

Smart Guns as a Part of Other Uniforms

Will the military ever adopt smart guns? If my answer to the civilian question was “no” then my answer to the military question is “hell no!” While you might think that soldiers have more in common with police than citizens, especially as the above-listed comparison points are concerned… in actuality their situation is wildly different from all others. Let’s consider men and women serving in the armed forces and how they rely on their firearms.

A soldier firing his Beretta M9 pistol

Military personnel have a daily routine with the following characteristics:

- They almost always wear the same uniform consistently while serving

- There is a very real chance that they will have to use their gun on any given day

- The vast majority of soldiers, sailors, marines, and airmen wear their sidearm prominently, in plain view

- Serving in the military (especially while deployed) routinely involves encounters with those who might do harm

At first glance, that list reads like almost a perfect and direct parallel to the Police Officer daily routine described above. So, then, why wouldn’t smart guns apply in this situation? Let’s delve a little more deeply and the answer should become very apparent.

Yes, military personnel often wear the same uniform everyday. Indeed, they are regularly held to a much more strict grooming standard than LEOs serving state-side and they typically equip their belts and vests with far more gear than law enforcement officers do. But, a great deal of this happens in-theater, far from reliable supply lines and the comforts of society. If RFID technology is operating with the use of extra batteries, for example, this small consideration could prove unbelievably difficult when serving in a forward area. It was hard enough for many serving in Iraq and Afghanistan recently to obtain adequate power for the night vision and thermal sensors… imagine the consternation among soldiers forced to harass supply officers and make trips to the PX just to ensure that their duty weapons would fire!

Also, while there is a chance that police officers will use their gun on any given day, many LEOs go from the academy to retirement without ever firing a single bullet outside of a police range during training and qualification. Active-duty military, particularly those serving in forward areas, are rarely so insulated from confrontation. Having a reliable weapon that will work each time & every time is an essential component of their life. The armed forces are not likely to adopt any firearm that has even the slightest chance of malfunctioning in a way that prevents it from firing.

While men and women serving in uniform prominently wear their firearms on the outside of their outfits, one can see that the possibility of a bad actor getting close enough to abscond with one is quite remote. Not only are potential hostiles kept well out of close proximity to soldiers, but military personnel are well-versed in hand-to-hand combat… any attempt to snatch something from them — particularly a weapon — is all but suicidal.

Above and beyond all other considerations, however, is the simple fact that service in the military — particularly during a time of conflict — is a chaotic and unpredictable affair in its harshest moments. Unclean conditions, dirty uniforms, sweat, and even blood smeared across an individual’s hands are routine as he or she trains a weapon upon enemy forces.

USMC 1st Sgt. (now Sgt. Maj.) Bradley Kasal is assisted out of a house in Fallujah. Despite being shot with seven rounds from an enemy AK47 and being littered with shrapnel from a grenade blast, he still clutches his Beretta M9 pistol and Ka-Bar knife.

Unless ordered, there is no retreat during combat. Often there are no additional forces to muster from a few blocks away, as with police. In the absence of backup, soldiers, sailors, marines, and airmen continue to fight while injured, while wounded, and even while clinging to life. If someone falls in the heat of battle, they are treated as rapidly and effectively as medical personnel can manage… and if they are combat-ineffective it is not unthinkable that their own firearms could be handed to others in their unit, who seek to lay down fire and repel hostiles until the engagement is concluded.

In a situation like that — where one must make every shot count and it’s entirely possible to be gripping the weapon of a brother- or sister-in-arms with bloodied, sand-caked hands — you’d better believe no single person in uniform (from the ground-pounders and grunts to the top brass) is the slightest bit interested in new technologies that might make a firearm marginally safer if there is even so much as a one in a million chance that it would fail to perform when needed most.

.

So What Will the Future Hold?

All in all, the idea of smartguns intrigues me. There may be at time when they are widely-adopted by police departments. I think the most interesting potential pertains to correctional officers. They will never be used in the military. And as for private citizens? While I don’t ever foresee laws that would prevent purchase or ownership (concerns about reverse-engineering and criminals attempting to design technologies to defeat them are too remote… but the idea of a Denial of Service attack against such guns is terrifying to me as I imagine squadcars all arriving on the scene of a bank robbery only to find all officers’ guns not working) I would not expect private citizens to adopt these guns.

Gun culture in the United States is deeply steeped in traditions relating to preparedness, self-reliance, and the protection of property and loved ones. Asking private citizens to rely on a technology that offers only the slightest of benefits while resulting in some very real risks and pitfalls is a tough sell. (The most die-hard and extreme members of the gun community are not sportsmen, but the survivalist/prepper types… you go ahead and try to sell them on the merits of a firearm that wouldn’t work in the event of an EMP blast.) Any attempt at mandating smart gun use legislatively would be akin to asking citizens to turn in all of their existing firearms… and we all know that will never happen, or at least such a directive would never be complied with.

Up until now, all of the changing trends in police firearm ownership and use have been mirrored in the civilian market because of how closely paralleled the interests and aims of those two groups tend to be. Smart gun usage, if it ever becomes mainstream for police, will not see a similar adoption because of the very significant ways in which private citizens’ lives are distinct from those of police.

.

Deviant Ollam is a security contractor from Philadelphia whose company provides services and training to both the private market and to government agencies. He has worked directly with police, military personnel, the FBI, the NSA, and given guest lectures to the cadets at the United States Military Academy at West Point. His grandfather was an enlisted sailor in the United States Navy, serving in the Pacific theater during World War II, and he then worked as a Special Agent for the Federal Government until his retirement. Deviant’s father was an officer in the United States Army who served during the Vietnam Conflict, later discharging to focus on the building of a private dental practice in New Jersey. Dev’s mother was a Registered Nurse for much of her life, and she wishes he was more widely-known by his given name as opposed to this silly hacker moniker.

Deviant has written multiple books and articles about physical security, lockpicking, and firearms and is a regular speaker at security conferences on these topics, as well. He likes both scotch and bourbon and will surely exchange small bottles of either for a spot on the firing line at the annual shooting event he runs in the Nevada Desert each summer.

.

.

.